RWANDA NZIZA NGOBYI IDUHETSE

Nzayisenga Adrien

Sunday, March 8, 2026

Iran yavuze ko ifite ubushobozi bwo kumara amezi atandatu ihanganye na Israel na Amerika

Kuki Amerika yahannye ingabo z'u Rwanda n'abajenerali bane

Ahavuye isanamu,

- Umwanditsi

Amerika yafatiye ibihano ingabo z'u Rwanda (RDF) n'abasirikare bakuru bane bo mu rwego rwa Jenerali kubera "ubufasha mu bikorwa butaziguye" ku mutwe w'inyeshyamba wa M23 urwanya ubutegetsi bwa Repubulika ya Demokarasi ya Congo (DRC).

Amerika ivuga ko ubwo bufasha burenga ku masezerano y'amahoro u Rwanda na DRC byashyizeho umukono i Washington DC ku itariki ya 4 Ukuboza (12) mu 2025, hagati ya Perezida w'u Rwanda Paul Kagame na Perezida wa DRC Félix Tshisekedi.

Abo basirikare ni:

- Umugaba mukuru w'ingabo z'u Rwanda Jenerali (Gen) Mubarakh Muganga

- Umugaba w'ingabo zirwanira ku butaka Jenerali Majoro (Maj Gen) Vincent Nyakarundi

- Maj Gen Ruki Karusisi ukuriye diviziyo ya gatanu wahoze ari umukuru w'umutwe w'ingabo zikora ibikorwa byihariye (Special Operations Force)

- Brigadiye Jenerali (Brig Gen) Stanislas Gashugi, umukuru w'umutwe w'ingabo zihariye

Leta y'u Rwanda ivuga ko ibabajwe n'ibi bihano by'Amerika "byibasira uruhande rumwe gusa birurenganya".

Perezida Kagame yavuze kuri RDC yahaye rugari FDLR n’umuhungu wa Habyarimana

Perezida Paul Kagame yagaragaje uburyo abo mu muryango wa Habyarimana cyane cyane umuhungu we bakomeje gukorera ingendo i Kinshasa muri Repubulika Iharanira Demokarasi ya Congo, mu mugambi wo gukorera mu ngata umutwe w’Iterabwoba wa FDLR wasize ukoze Jenoside yakorewe Abatutsi mu Rwanda.

Umukuru w’Igihugu yabigarutseho mu kiganiro yagiranye n’abadipolomate bahagarariye ibihugu byabo mu Rwanda, ku wa 6 Werurwe 2026, ubwo yabakiraga ku meza.

Yasobanuye ko uyu mutwe w’iterabwoba ukomeje kuvuna umuheha ukongezwa undi muri Repubulika Iharanira Demokarasi ya Congo, wubakiye ku ngengabitekerezo ya Jenoside kandi ukomeje kuwukongeza mu Karere ari ikibazo gihangayikishije u Rwanda.

Ati “Impungenge z’umutekano wacu zishingiye ku gukomeza kubaho kwa FDLR n’ingengabitekerezo yayo y’ubutagondwa bw’urugomo, ari na yo ngengabitekerezo ya Jenoside. Birababaje kubona bigaragara ko hari abayishyigikira no mu karere n’ahandi.”

Perezida Kagame yerekanye ko kuva FDLR yagera muri RDC, ibitero igaba ku Rwanda mu bihe bitandukanye byahitanye ubuzima bw’abatari bake mu gihugu.

Yibukije uburyo Guverinoma ya RDC yemeye guha ubufasha bwose FDLR haba mu bya dipolomasi, kuyiha intwaro no kuyishyira mu gisirikare cya Repubulika Iharanira Demokarasi ya Congo, FARDC.

Ati “Guverinoma ya RDC yahaye iri tsinda uburinzi mu bya politiki n’inkunga y’amafaranga, ndetse inaryinjiza no mu nzego zayo za gisirikare, aho ubu rikorera nta nkomyi kandi ntawe uribaza ibyo rikora.”

Yanavuze kandi ku bucuti bukomeye buri hagati y’umuhungu w’uwahoze ari Perezida w’u Rwanda n’umutwe wa FDLR wiyemeje guhuza umugambi na yo ndetse kuri ubu akomeje gusura RDC mu gushimangira ubushuti bwe na FDLR.

Ati “Umuhungu w’uwahoze ari Perezida w’u Rwanda, wagejeje iki gihugu muri Jenoside, n’abandi bafatanyije, bakomeje gusura Kinshasa mu rwego rwo kwagura imikoranire yabo na FDLR, kandi bagahabwa ikaze.”

Yavuze ko u Rwanda rwakomeje kugaragaza icyo kibazo ku ruhando mpuzamahanga, ariko ugasanga ibyafasha ku kwita ku kibazo muzi byazana igisubizo byirengagizwa nkana.

Perezida Kagame ariko yavuze ko bitewe n’amateka y’u Rwanda n’aho ruherereye bisaba kurinda umutekano w’imipaka yarwo.

Yongeye gushimangira ko umutwe wa FDLR atari abarwanyi bawugize gusa ahubwo ko ingengabitekerezo ya Jenoside ukomeje gukwirakwiza ari yo iteye inkeke, yanagejeje ku kwibasira Abanye-Congo b’Abatutsi.

Umukuru w’Igihugu kandi yashimye inzego z’umutekano z’u Rwanda ku kazi gakomeye zikora mu gucunga umutekano w’igihugu hirindwa ko abaturage bacyo bakongera kwisanga mu kaga.

Kugeza ubu muri RDC habarurwa abarwanyi ba FDLR bari hagati ya 7000 n’ibihumbi 10.

Mu mpera za 2025 byamenyekanye ko Perezida Félix Tshisekedi Tshilombo wa Repubulika Iharanira Demokarasi ya Congo n’umuryango wa Juvénal Habyarimana uba mu Bufaransa, batangiye kunoza umugambi wo guhungabanya umutekano w’u Rwanda babinyujije mu mutwe w’iterabwoba wa FDLR.

Amakuru yizewe yavugaga ko Tshisekedi n’umuryango wa Habyarimana bateganyaga guha FDLR ibikoresho bihagije, bayifashe kubona abarwanyi bashya, kandi ihabwe ubuyobozi bushya; aho umuhungu wa Habyarimana, Jean-Luc Habyarimana azaba ari we muyobozi mukuru w’uyu mutwe.

Umuntu wa hafi y’ibiro bya Perezida wa RDC yahishuye ko ubutegetsi bw’iki gihugu buri gukorana na Jean-Luc, abanyamuryango b’ihuriro RNC riyoborwa na Kayumba Nyamwasa n’iyiyita ‘Guverinoma y’u Rwanda iri mu buhungiro’ iyoborwa na Thomas Nahimana wabaye Padiri.

Byagaragajwe ko Tshisekedi yateganyaga inama yo ku rwego rwo hejuru i Kinshasa mu ntangiriro za 2026, yagombaga guhuza abantu bo mu mitwe y’iterabwoba biyita abatavuga rumwe n’ubutegetsi bw’u Rwanda, kugira ngo bareme ihuriro rifite igisirikare gikomeye gishobora guhungabanya umutekano w’u Rwanda, kikaba cyanakuraho ubutegetsi bwarwo.

Ku wa 4 Gashyantare 2026, Tshisekedi yari muri Amerika mu gushyira imbaraga mu bukangurambaga busaba abagize Inteko Ishinga Amategeko b’Abanyamerika gusunikira ubutegetsi bw’icyo gihugu gufatira ibihano u Rwanda kubera uruhare arushinja mu ntambara yo mu burasirazuba bwa RDC.

Bisa n’aho urugendo rwe rutamuhiriye kuko yeretswe ko kugira ngo haboneke amahoro arambye, Leta ya RDC igomba gusenya umutwe w’iterabwoba wa FDLR nk’uko amasezerano y’amahoro ya Washington abiteganya ndetse na Wazalendo.

Itangazo ryagiraga riti “Kugira ngo umutekano urambye uboneke, RDC igomba gukora ibyo isabwa mu guhosha amakimbirane, ifata ingamba zifatika kuri FDLR n’imitwe y’abagizi ba nabi ya Wazalendo ikorera abaturage ubugizi bwa nabi.”

U Rwanda rwagaragaje kenshi ko rudashobora gukuraho ingamba z’ubwirinzi mu gihe umutwe wa FDLR ugihabwa intebe n’ubutegetsi bwa RDC kandi ari ikibazo ku mutekano warwo n’Akarere k’Ibiyaga Bigari.

Saturday, February 28, 2026

Amerika yanze ko Venezuela yishyurira Maduro umwunganizi

Umunyamategeko wa Nicolás Maduro ku byaha ashinjwa na Leta Zunze Ubumwe za Amerika byo gucuruza ibiyobyabwenge, Barry Pollack, yatangaje ko ubutegetsi bwa Trump bwanze ko Venezuela imwishyurira ikiguzi cy’ubwunganizi.

Barry Pollack yabibwiye umucamanza w’Urukiko rwa Manhattan mu butumwa yohereje yifashishije email.

Yagaragaje ko Minisiteri y’Imari ya Amerika yahagaritse uburenganzira bwo kwishyura ikiguzi cy’ubwunganizi bwa Maduro mu gihe Guverinoma ya Venezuela yasabaga kumwishyurira n’umugore we Cilia Flores.

Maduro n’umugore we bafungiwe i New York nyuma y’uko batawe muri yombi n’icyo gihugu mu bitero byagabwe kuri Venezuela ku wa 3 Mutarama 2026.

Abo bombi, Amerika ibashinja ibyaha birimo ubucuruzi bw’ibiyobyabwenge n’ibikorwa by’iterabwoba.

Uyu munyamategeko yavuze ko ku wa 9 Mutarama, hatanzwe uburenganzira kuri Guverinoma ya Venezuela bwo kwishyura amafaranga y’abanyamategeko ariko nyuma y’amasaha atatu gusa bugahita bwongera gukurwaho ntihanasobanurwe impamvu.

Pallock yavuze ko yasabye ibiro bishinzwe kugenzura umutungo w’amahanga ku wa 11 Gashyantare korohereza Venezuela ku buryo yakuzuza inshingano zayo zo kwishyura abunganizi nubwo bitarakorwa.

Yavuze ko mu gihe bitakorwa bityo, Maduro nta bushobozi yabona bwo kwishyura abamwunganira ahubwo ko yazasaba urukiko ubufasha kugira ngo abashe kunganirwa.

Mu kirego cy’impapuro 25, Maduro ashinjwa gukorana n’amatsinda y’aba-Cartels ndetse n’abasirikare batandukanye mu kwinjiza ibiyobyabwenge byo mu bwoko bwa Cocaine muri Amerika.

Harimo kandi ibirego byo gukubita no gukomeretsa, ubwicanyi n’ibindi.

Mu gihe byabahama Maduro n’umugore we bahanishwa igihano cy’igifungo cya burundu.

Ubwo yagezwaga imbere y’urukiko ku wa 5 Mutarama 2026, Maduro yahakanye ibyaha byose ashinjwa birimo no kuba intandaro y’ibiyobyabwenge bitundirwa muri Leta Zunze Ubumwe za Amerika.

U Rwanda ntirwumva uburyo Gen Ekenge akidegembya nyuma y’imvugo zibiba urwango

Minisitiri w’Ububanyi n’Amahanga n’Ubutwererane, Ambasaderi Olivier Nduhungirehe, yahamije ko amagambo y’urwango yibasira Abanye-Congo bo mu bwoko bw’Abatutsi ashyigikiwe n’ubutegetsi bwa Repubulika Iharanira Demokarasi ya Congo.

Mu nama y’akanama k’Umuryango w’Abibumbye gashinzwe uburenganzira bw’ikiremwamuntu yabereye i Genève mu Busuwisi, Minisitiri Nduhungirehe yagaragaje ko ibikorwa byibasira amoko n’ingengabitekerezo ya jenoside bikomeje gukwirakwira muri RDC.

Ati “Mu myaka myinshi, akarere kacu kashegeshwe n’ubuhezanguni bushingiye ku moko n’ingengabitekerezo ya jenoside. Uyu munsi, ibi bikorwa byongeye kugaragara mu burasirazuba bwa RDC, aho ubugizi bwa nabi buri gukorerwa abanyantege nke.”

Minisitiri Nduhungirehe yatangaje ko Abanye-Congo bo mu bwoko bw’Abatutsi barimo Abanyamulenge batuye mu ntara ya Kivu y’Amajyepfo bari kugabwaho ibitero n’imitwe yitwaje intwaro ishyigikiwe na Leta ya RDC, ingabo z’iki gihugu na zo zikabigiramo uruhare.

Ati “Imidugudu yose iri kuraswa n’indege na drones. Inzu zaratwitswe zirakongoka, zirasenywa, imiryango yarahunze ibitewe n’ubukangurambaga bugamije kuyirukana ku butaka bwa gakondo. Muri Kivu y’Amajyepfo, Abanyamulenge bajyanywe ahantu badashobora kurema amasoko, kujya ku mashuri, kuragira no kubona serivisi z’ubuvuzi.”

Yagaragaje ko u Rwanda rwatanze impuruza ku magambo y’urwango akomeje gukwirakwira muri RDC, ariko ko nta gifatika cyakozwe, ibyatumye abo muri Leta ya RDC n’imitwe yitwaje intwaro ishyigikiye byongera imbaraga muri ibi bikorwa bigamije ubugizi bwa nabi.

Mu Ukuboza 2025, uwahoze ari Umuvugizi w’ingabo za RDC, Gen Maj Sylvain Ekenge Bomusa, yavugiye kuri televiziyo y’igihugu (RTNC) ko abagore b’Abatutsikazi batajya babyarana n’abo badahuje ubwoko, asaba abagabo bo muri RDC kubitondera.

Minisitiri Nduhungirehe yasobanuriye akanama ka Loni gashinzwe uburenganzira bw’ikiremwamuntu ko amagambo Gen Ekenge yavugiye kuri RTNC yari yateguwe, kandi ko ari mu murongo wa Leta ya RDC itarigeze imukurikirana mu butabera.

Ati “Yari yateguwe mbere. Yayavugiye mu ruhame, yumvikana mu gihugu hose. Ni amagambo y’urwango ashyigikiwe na Leta, kandi Gen Maj Ekenge yahagaritswe by’agateganyo nyuma y’aya magambo, biteza uburakari ariko ntiyakurikiranywe n’ubutabera. Ayo magambo atesha agaciro ubwoko bwose, agashyira abagore mu kaga gakomeye. Amateka agaragaza ko iyo aya magambo afashwe nk’asanzwe, ubugizi bwa nabi bukurikiraho.”

Yagaragaje ko u Rwanda rugaragaza izi mpungenge rushingiye ku mateka rwanyuzemo, kuko nyuma y’igihe amagambo y’urwango akwirakwira, habayeho Jenoside yakorewe Abatutsi mu 1994, yatwaye ubuzima bw’abarenga miliyoni 1 mu gihe cy’iminsi 100.

Minisitiri Nduhungirehe yasabye akanama ka Loni gashinzwe uburenganzira bw’ikiremwamuntu kwamagana bikomeye amagambo y’urwango akomeje gukwirakwizwa n’abarimo abo muri Leta RDC, kagasaba ko bakurikiranwa n’ubutabera kandi abaturage bari mu kaga bakagezwaho ubutabazi vuba, nta kubogama.

Sunday, January 18, 2026

Ruanda-Urundi

- Article wrote by Nzayisenga Adrien, 2024

Ruanda-Urundi (French pronunciation: [ʁwɑ̃da uʁundi]),[a] later Rwanda-Burundi, was a mandate and later trust territory ruled by Belgium between 1916 and 1962.

Once part of German East Africa, the region was occupied by troops from the Belgian Congo during the East African campaign in World War I. It was administered by Belgium under military occupation from 1916 to 1922. It was subsequently awarded to Belgium as a Class-B Mandate under the League of Nations in 1922 and became a Trust Territory of the United Nations in the aftermath of World War II and the dissolution of the League. In 1962, Ruanda-Urundi became the two independent states of Rwanda and Burundi.

History

editRuanda and Urundi were two separate kingdoms in the Great Lakes region before the Scramble for Africa. In 1897, the German Empire established a presence in Rwanda with the formation of an alliance with the king, beginning the colonial era.[1] They were administered as two districts of German East Africa. The two monarchies were retained as part of the German policy of indirect rule, with the Ruandan king (mwami) Yuhi V Musinga using German support to consolidate his control over subordinate chiefs in exchange for labour and resources.[2]

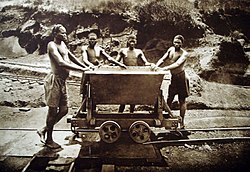

Belgian military occupation, 1916–1922

editWhen World War I broke out in 1914, German colonies were originally meant to preserve their neutrality as mandated in the Berlin Convention, but fighting soon broke out on the frontier between German East Africa and the Belgian Congo around Lakes Kivu and Tanganyika.[2] As part of the Allied East African campaign, Ruanda and Urundi were invaded by a Belgian force in 1916.[2] German forces in the region were small and hugely outnumbered. Ruanda was occupied over April–May and Urundi in June 1916. By September, a large portion of German East Africa was under Belgian occupation reaching as far south as Kigoma and Karema and as far eastwards as Tabora all in modern-day Tanzania.[2]

In Ruanda and Urundi, the Belgians were welcomed by some civilians, who were opposed to the autocratic behaviour of the kings.[2] In Urundi, much of the population fled or went into hiding, fearful of war.[3] Much of the Swahili trader community which resided along the shores of Lake Tanganyika fled towards Kigoma, as they had long been commercial rivals with Belgian traders and feared retribution.[4] The territory captured was administered by a Belgian military occupation authority ("Belgian Occupied East African Territories") pending an ultimate decision about its political future. An administration, headed by a Royal Commissioner, was established in February 1917 at the same time as Belgian forces were ordered to withdraw from the Tabora region by the British.[citation needed]

While the Germans had begun the practice of conscripting labour from the Ruandans and Urundians during the war, this was limited since the German administration considered sustaining a local labour force logistically challenging. The Belgian occupation force expanded labor conscription;[5] 20,000 men were drafted to act as porters for the Mahenge offensive, and of these only one-third returned home.[6] Many died due to malnourishment and disease.[7] The new labour practices caused some locals to regret the departure of the Germans.[8]

League of Nations mandate, 1922–1946

editThe Treaty of Versailles in the aftermath of World War I divided the German colonial empire among the Allied nations. German East Africa was partitioned, with Tanganyika allocated to the British and a small area allocated to Portugal. Belgium was allocated Ruanda-Urundi even though this represented only a fraction of the territories already occupied by the Belgian forces in East Africa. Belgian diplomats had originally hoped that Belgian claims in the region could be traded for territory in Portuguese Angola to expand the Congo's access to the Atlantic Ocean. This proved impossible and the League of Nations officially awarded Ruanda-Urundi to Belgium as a B-Class Mandate on 20 July 1922. The mandatory regime was also controversial in Belgium and it was not approved by Belgium's parliament until 1924.[9] Unlike colonies which belonged to its colonial power, a mandate was theoretically subject to international oversight through the League's Permanent Mandates Commission (PMC) in Geneva, Switzerland.[citation needed]

Administratively, the mandate was divided into two pays, Ruanda and Urundi, each under the nominal leadership of a Mwami as customary ruler. The city of Usumbura (modern-day Bujumbura) and its adjoining townships were classified separately as centres extra‑coutumiers, while the pays were subdivided into territories.[10]

After a period of inertia, the Belgian administration became actively involved in Ruanda-Urundi between 1926 and 1931 under the governorship of Charles Voisin. The reforms produced a dense road-network and improved agriculture, with the emergence of cash crop farming in cotton and coffee.[11] However, four major famines did ravage parts of the mandate after crop failures in 1916–1918, 1924–26, 1928–30 and 1943–44.[citation needed] The Belgians were far more involved in the territory than the Germans, especially in Ruanda. Despite the mandate rules that the Belgians had to develop the territories and prepare them for independence, the economic policy practised in the Belgian Congo was exported eastwards: the Belgians demanded that the territories earn profits for their country and that any development must come out of funds gathered in the territory. These funds mostly came from the extensive cultivation of coffee in the region's rich volcanic soils.

To implement their vision, the Belgians extended and consolidated a power structure based on indigenous institutions. In practice, they developed a Tutsi ruling class to formally control a mostly Hutu population, through the system of chiefs and sub-chiefs under the overall rule of the two Mwami. Belgian administrators were influenced by the so-called Hamitic hypothesis which suggested that the Tutsi were partially descended from a Semitic people and were therefore inherently superior to the Hutu who were seen as purely African.[12] In this context, the Belgian administration preferred to rule through purely Tutsi authorities therefore further stratifying the society on ethnic lines. Hutu anger at the Tutsi domination was largely focused on the Tutsi elite rather than the distant colonial power.[13] Musinga was deposed by the administration as mwami of Ruanda in November 1931 after being accused of disloyalty.[14] He was replaced by his son Mutara III Rudahigwa.

Although promising the League it would promote education, Belgium left the task to subsidised Catholic missions and mostly unsubsidised Protestant missions. Catholicism expanded rapidly through the Rwandan population in consequence. An elite secondary school, the Groupe Scolaire d'Astrida, was established in 1929. As late as 1961, fewer than 100 people from Ruanda-Urundi had been educated beyond the secondary level.[15]

United Nations trust territory, 1946–1962

editThe League of Nations was formally dissolved in April 1946, following its failure to prevent World War II. It was succeeded, for practical purposes, by the new United Nations (UN). In December 1946, the new body voted to end the mandate over Ruanda-Urundi and replace it with the new status of "Trust Territory". To provide oversight, the PMC was superseded by the United Nations Trusteeship Council. The transition was accompanied by a promise that the Belgians would prepare the territory for independence, but the Belgians felt the area would take many decades to be ready for self-rule and wanted the process to take enough time before happening.

In 1961, the Belgian administration officially renamed Ruanda-Urundi as Rwanda-Burundi.[16]

Independence came largely as a result of actions elsewhere. African anti-colonial nationalism emerged in the Belgian Congo in the late 1950s and the Belgian Government became convinced they could no longer control the territory. Unrest also broke out in Ruanda where the monarchy was deposed in the Rwandan Revolution (1959–1961). Grégoire Kayibanda led the dominant and ethnically defined Party of the Hutu Emancipation Movement (Parti du Mouvement de l'Emancipation Hutu, PARMEHUTU) in Rwanda, while the equivalent Union for National Progress (Union pour le Progrès national, UPRONA) in Burundi attempted to balance competing Hutu and Tutsi ethnic claims. The independence of the Belgian Congo in June 1960 and the accompanying period of political instability further drove nationalism in Ruanda-Urundi. The assassination of the UPRONA leader Louis Rwagasore (also Burundi's crown prince) in October 1961 did not halt this movement. After hurried preparations which included the dissolution of the monarchy in the Kingdom of Rwanda in September 1961, Ruanda-Urundi became independent on 1 July 1962, broken up along traditional lines as the independent Republic of Rwanda and Kingdom of Burundi. It took two more years before the government of the two became wholly separate and a further two years until the proclamation of the Republic of Burundi.

Colonial governors

editRuanda-Urundi was initially administered by a Royal Commissioner (commissaire royal) until the administrative union with the Belgian Congo in 1926. After this, the mandate was administered by a Governor (gouverneur) located at Usumbura (modern-day Bujumbura) who also held the title of Vice-Governor-General (vice-gouverneur général) of the Belgian Congo. Ruanda and Urundi were each administered by a separate resident (résident) subordinate to the Governor.

- Royal Commissioners (1916–1926)

- Justin Malfeyt (November 1916 – May 1919)

- Alfred Marzorati (May 1919 – August 1926)

- Governors (1926–1962)

- Alfred Marzorati (August 1926 – February 1929)

- Louis Postiaux (February 1929 – July 1930)

- Charles Voisin (July 1930 – August 1932)

- Eugène Jungers (August 1932 – July 1946)

- Maurice Simon (July 1946 – August 1949)

- Léo Pétillon (August 1949 – January 1952)

- Alfred-Marie Claeys-Boùùaert (January 1952 – March 1955)

- Jean-Paul Harroy (March 1955 – January 1962)

For a list of residents, see: List of colonial residents of Rwanda and List of colonial residents of Burundi.

- Kings (abami) of Ruanda

- Yuhi V Musinga (r. November 1896 – November 1931)

- Mutara III Rudahigwa (r. November 1931 – July 1959)

- Kigeli V Ndahindurwa (r. July 1959 – September 1961, when the Ruandan monarchy was abolished)

- Kings (abami) of Urundi

- Mwambutsa IV Bangiricenge (r. December 1915 – July 1966)

Maps

edit- Territory of Ruanda-Urundi

- In 1929

- In 1938

RWANDA NZIZA NGOBYI IDUHETSE

Iran yavuze ko ifite ubushobozi bwo kumara amezi atandatu ihanganye na Israel na Amerika

Umutwe w’ingabo za Iran uzwi nka Islamic ‘Revolutionary Guard Corps, IRGC’, watangaje ko iki gihugu gifite ubushobozi bwo kumara amezi atan...

-

The Abiru ( Kinyarwanda for royal ritualists ) are the members of the privy council of the monarchy of Rwanda . They emanate f...

-

Rwigema was born in Gitarama , in southern Rwanda. Considered a Tutsi, in 1960 he and his family fled to Uganda and settled in a refug...

-

Yuhi Musinga ( Yuhi V of Rwanda , 1883 – 13 January 1944) [ 5 ] was a king ( umwami ) of Rwanda who came to power in 1896 and collabor...